Kaela B. directed the field operations for Frankie for Greenbelt in 2025. She has been a DSA member since 2021 and previously stewarded the Member Engagement Department in the Metro DC chapter. Her professional background encompasses communications, research operations, project management, and organizational behavior. Kaela has lived in DC since 2015.

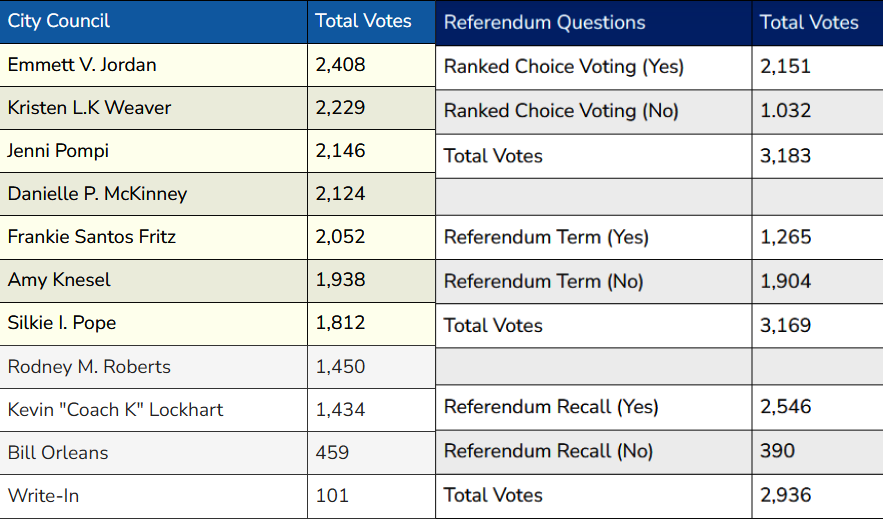

IN 2025, I DIRECTED THE FIELD OPERATIONS for newly elected Greenbelt, Maryland, City Councilmember Frankie Santos Fritz, the first candidate who was already a committed member of Metro DC DSA to win an elected seat in several years. One hundred twenty-two volunteers knocked more than 17,454 doors, winning more votes than three incumbents as a first-time candidate. No newcomer has defeated even one incumbent for Greenbelt City Council since 1985.

Some of what made this victory possible was totally out of our control: the density and demographics of the city of Greenbelt, the particulars of the incumbents, and Frankie’s professional history and presentation. But one thing the campaign could control was the way we recruited and deployed volunteers to speak to the community about Frankie’s platform — and persuade them to vote in the off-year election.

So often, high-energy projects like the Frankie campaign attract bright-eyed, committed people who are eager to help. And in the fast pace of an electoral campaign, it is difficult to create entry points for these volunteers to take on real responsibility, even when they are obviously ripe to do so. So this cycle, I and other core organizers of the campaign focused on building an engagement ladder to give participants opportunities to organize and run canvasses, and even mentor other volunteers.

During the campaign, we aimed to remove the obstacles to higher levels of engagement for newcomers, and to create the conditions for their motivation to carry them upwards in leadership. As a result, several people who were new to DSA and electoral work became core members of Frankie’s campaign. To achieve this, we invited newcomers to have real responsibilities, systematized the process for onboarding, and made sure to adjust processes based on volunteer feedback.

In July, the MDC DSA Electoral Working Group held a two-day training to prepare both DSA members and the DSA-curious (of any experience level) for the election season. At the end of the training, facilitators split participants into groups by their availability over the next three weeks, and on the spot, they were assigned a date to help organize what would be their first canvassing shift.

There was a palpable din of excitement as participants were asked to apply the information that had just been presented to them, in an instant transforming from observers to “doers.” Several members later cited this as the best part of the training. Armed with written resources, and with an experienced guide assigned to each of the five groups, attendees all launched successful canvasses over the next three weeks.

Importantly, identifying candidates for this next step didn’t stop at the time of the training. Organizers in the campaign kept an eye out for people who seemed enthusiastic and showed up to a second canvass. Most who met this description only required a little encouragement to agree to launch a canvass, especially if they were asked to support on a specific date by someone in a visible leadership position.

Because newcomers took responsibility over an entire canvass and not just one rote aspect of it, they had the opportunity to see both the context and the result of their work. The context was that the campaign needed help to get Frankie on the Greenbelt City Council to fight for working-class Greenbelters, and the best way to help was to run a canvass. The result was the occurrence of the event: people showed up, knocked doors, had conversations with real people, and communed afterwards. By making sure that members participated in the beginning, middle, and end of their work, we saw them become progressively committed to the campaign, even as general attendance ebbed.

The best time to train someone new is “on the job,” when their new skills can be applied immediately. This is also usually when the people qualified to give such a training are the busiest, which is especially true in the hectic pace of an electoral campaign.

This has real consequences. Since training new leaders isn’t immediately necessary to continue moving forward in the campaign, it frequently doesn’t happen at all. At the end of the campaign, it is the same 5-10 people who have built up all the organizing experience. In order to get around this perennial issue, I proposed a role called the “coordinator.” The coordinator’s purpose was to make it possible for a new person to organize and launch canvasses, in a role called the “field lead.”

Coordinators set up meetings and text threads that groups used to organize canvasses, offered guidance through the week leading up to canvasses, tackled all the tasks that required more internal chapter know-how than new people could be expected to have, and offered support at the canvasses themselves. In essence, coordinators held all the higher-level responsibilities necessary to make it possible for a new person to launch a canvass.

Coordinators needed to understand how to use Metro DC DSA's resources to recruit people to attend a canvass, and they needed to be able to answer questions on how to run a canvass. And ideally, they had a sense of when to intervene with guidance, and when to encourage their field leads to problem solve on their own. Not an easy task!

The role, which a total of nine people filled, went through some transformation over the course of the campaign. Even coordinators with a grip on both recruitment and electoral organizing needed a walkthrough of what they were being asked to do. Another discovery was that only first-time field leads really needed one-to-one coaching; once they got over the initial nerves, they didn’t need as much support.

Becoming a coordinator was also the final stage of the engagement ladder. Ultimately, four field leads graduated to fill the coordinator role by the end of the campaign.

The beauty of an electoral campaign is that each weekend is an experiment, and every week is an opportunity to iterate. One example on the Frankie campaign: the work of running a canvass was initially split up into four roles: field captain, field assist, turnout captain, and turnout assist. However, it quickly became clear that the roles weren’t helpful: people wanted to jump in in whatever ways they had capacity for instead of being constrained to a set group of tasks.

Responding to this issue, core organizers developed a painstaking checklist that ordered all tasks by deadline. The canvass organizers were asked to meet at least two days before their event to divide the responsibilities among them.

Throughout the campaign, I followed up with the field leads and coordinators to find out how their canvasses went. Even a simple text exchange could give me information to tighten up the checklist each week. It also created a more mutual relationship: members weren’t just work horses for the campaign, they were helping us to improve both their experience and the outcome of their efforts.

Setting aside time to evaluate what was effective (and what was not) was crucial to designing a field program that made sense for the context we were working in. It also required being humble and responsive to the perspectives of people all along the engagement ladder, instead of clinging to a grand theory of how things should work and faulting individual volunteers for the failures of the system.

Inviting members to launch their own canvass required the core organizers to loosen their grip on control and trust relative newcomers with the details. We had to have faith that if participants flaked or teams malfunctioned (which they certainly did at times), the risk was worth giving people autonomy over their work. With ample guidance, clear goals, and a little bit of caution thrown to the wind, the campaign had 31 first-timers help to launch canvasses over the course of Frankie’s campaign.

New members often struggle to find their place in DSA, and likewise, veteran members can struggle to delegate their work and identify new leaders. The engagement ladder within Frankie’s campaign was designed to counteract those problems: starting out with clear, graduated steps in responsibility and developing a system for supporting new people helped to build a team that sustained itself. The campaign stood strong despite core organizers going on extended travel, getting new jobs, transitioning to other pursuits, and simply needing a break. Instead of just doing the work itself, our focus was to teach and empower others to take on the mantle so that when we needed to step back, we could.

The majority of base-building organizations struggle to grow large enough to have political influence, and DSA is no exception. Answering that thorny question — how to burst through the cap of around 300 active members in our chapter at any given time — is central to achieving our organization’s aspirations. When highly committed members reorient from “doing the work” to enabling others to do it, suddenly our organization can scale and sustain itself beyond the current cohort of leaders. In Frankie’s campaign, core organizers worked to build the conditions for new members to not only learn organizing skills but to be self-motivated, helping them wield the confidence necessary to be creative and problem solve. The way we created these conditions could be an interesting model for upcoming electoral organizing and other formations within our chapter.