Andrea Crooms is a member of PG County Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), Southern Maryland DSA, former National DSA EcoSoc/Green New Deal Steering Committee member, and former director of the Prince George’s County Department of Environment.

THE EXPONENTIAL GROWTH of artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and digital surveillance is fueling a parallel explosion in the physical infrastructure that powers all three: the data center. Often mystified as an ethereal "cloud," this infrastructure is profoundly material, consuming vast tracts of land, staggering amounts of energy and water, and billions of dollars in public subsidies. Data center development represents a new frontier of extractive capitalism. But there is another way: a socialist approach that rejects the corporate model of data center development and instead fights for democratic control, a rejection of corporate welfare, and a vision of technology that serves people and the planet, not profit. This alternative vision can be seen in the fight against data centers by left-aligned organizations across the Washington metropolitan region (DMV), most specifically in Prince George’s County, Maryland. There, socialist and environmental justice organizations have banded together to form a powerful coalition opposing a specific data center and demanding transparency and accountability before other projects are considered, as detailed in local reporting on the community opposition.

The current paradigm of data center development is a textbook case of 21st-century extractivism. As scholar Thea Riofrancos argues in Resource Radicals (2020), extractivism is not limited to mining; it is a "mode of accumulation" based on the large-scale removal of resources for export, with benefits accruing to a narrow elite while costs are socialized across communities and ecosystems. This extractivist model functions by design: the massive consumption of electricity, water, and land inherently creates infrastructure strains and environmental debts that are offloaded onto the public sphere. We all share the bill for the capitalists roads and grid upgrades (socialized costs), but they don't pay for the pollution or water scarcity they create (an externality).

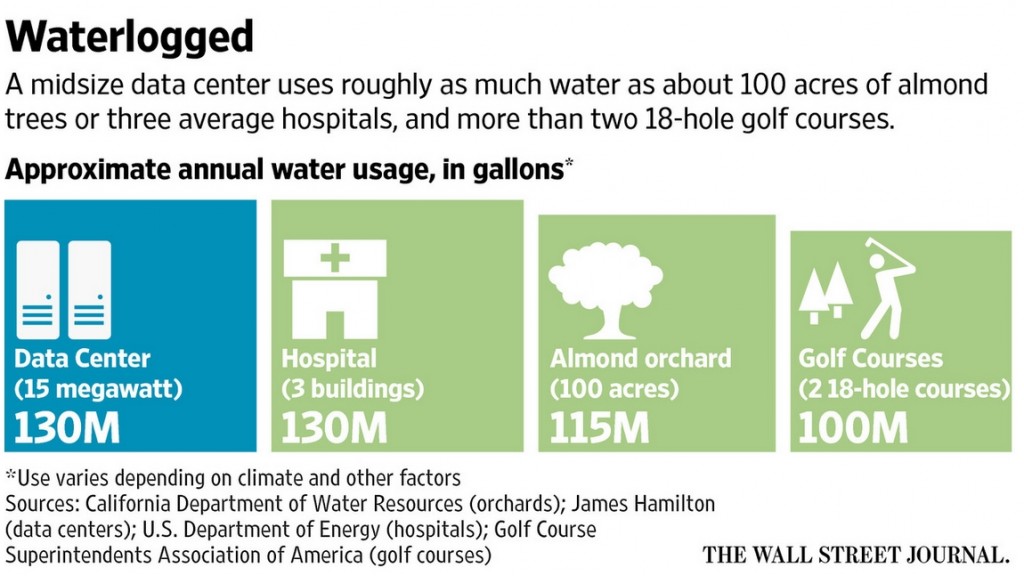

Data centers represent a contemporary form of infrastructural extractivism. First, they extract enormous volumes of energy and water, with a single facility often consuming power equivalent to hundreds of thousands of homes and millions of gallons of water daily for cooling. This immense, concentrated demand strains public utility grids and local watersheds, driving up costs for all ratepayers. Crucially, the massive capital investment required for grid expansion to support this corporate demand is routinely socialized, forcing the public to subsidize the very infrastructure used for their own exploitation.

Furthermore, this extraction extends to land and community health, as data centers are frequently sited in working-class and majority Black and brown communities like Prince George's County. This continues a long history of environmental racism, where communities historically denied investment are targeted for destructive projects. The resulting noise, light pollution, loss of green space, and industrial blight degrade quality of life, constituting a modern form of "sacrifice zoning" (Klein, 2019).

Finally, this system extracts financial resources directly from the public treasury through substantial local and state tax abatements and subsidies granted to corporations like Amazon Web Services and Google, draining public coffers. The inevitable budget shortfalls created by these deals are then passed on to the working class through higher property and sales taxes or cuts to essential services like schools and public transit.

Socialists are unwavering in their solidarity with organized labor. However, the data center boom presents a complex dilemma. Building trades unions often support these projects based on the promise of high-quality, unionized construction jobs — a vital source of work in an inequitable economy.

The socialist task is to navigate this tension with strategic clarity. We must acknowledge the material need for union jobs while challenging the framework that pits short-term labor gains against the long-term health of the community and the climate. Our opposition is not to construction workers earning a living, but to a model of development that creates mostly temporary construction jobs while providing few permanent operations jobs, almost universally nonunion, and which undermines the community conditions — well-funded schools, affordable utilities, a healthy environment — that those same workers and their families rely on.

The goal is to transcend this false choice between good jobs and healthy communities. Our demand must be for development that serves both the immediate need for good jobs and the long-term need for community well-being.

The apparent alignment of construction trade unions (e.g., IBEW, Pipefitters) with capital in support of data center development, against the wishes of segments of the community and environmental advocates, is a predictable outcome of structural economic pressures and a specific model of unionism. This dynamic can be understood through the lens of sectional interest, the pursuit of endless growth, and the historical divergence between "business" and "social" unionism.

Building trades unions operate primarily on a model of "business unionism." This model, according to analysis by labor scholars, prioritizes the immediate economic interests of a union's dues-paying members — wages, benefits, and job security — over broader class-wide or social solidarity (Lichtenstein, 2002). The consequences of this strategy are clear in our present moment. The sheer scale and capital intensity of data centers represent a bonanza of high-wage, multi-year work. The union's institutional survival and success become tied to the success of the capitalist project. Building trades unions become, in effect, a junior partner in the development, defending the capitalist project against community opposition. This "business unionism” alliance, while securing short-term gains for a specific segment of workers, represents a strategic failure for the working class as a whole, as it fractures the very coalitions necessary to challenge capital's power and win a future that serves all workers and communities.

This dependency places unions on what environmental sociologists call the "treadmill of production" (Longo, Clausen, & Clark, 2015). This theory posits that corporations, workers, and the state become locked into a system that requires continuous growth and capital investment, even when it is ecologically destructive. For the union, stopping the treadmill means their members lose their livelihoods, creating a form of "job blackmail" (Brecher, 1993) where they feel compelled to accept environmentally problematic projects. The union thus advocates for its sectional interest — the jobs of its members — in direct conflict with the universal interests of the wider working class, who bear the burdens of strained infrastructure, environmental costs, and altered community character.

This conflict mirrors historical labor-environmental divides, most recently visible in the support of building trades unions for the Keystone XL pipeline against a coalition of climate activists, Indigenous communities, and other social movements (Weis, Russell, & Black, 2015). The result is a political schism where the legitimate need for good jobs is pitted against the equally legitimate demands for environmental justice and democratic community control (Cole & Foster, 2001).

A resolution to this contradiction requires moving beyond the "jobs versus environment" framework. Advocates for a just transition, such as the DSA’s Green New Deal effort and the Climate Justice Alliance, argue that the demands of the activists opposing these environmental injustices cannot simply be "no," but must be a plan for "better, and different." For data centers, this involves fighting for transformative conditions, such as mandates for 100% renewable energy for data centers, closed-loop water systems, and legally binding community benefits agreements — or revolutionary change in the form of public ownership and control of data center infrastructure. The goal is to fuse the immediate material interests of workers with the long-term ecological and social interests of the community, creating a coalition powerful enough to challenge capital's agenda and demand a development model that serves the many, not the few.

The present-day, extractive model of data center development is sold to revenue-starved communities on a dual promise: that data centers will provide a massive influx of public funds, and that enormous public subsidies are a necessary investment to unlock this revenue. This initiates a familiar, self-defeating cycle.

First, in the “race to the bottom,” municipalities desperate for new revenue offer ever-larger tax breaks to attract development, a dynamic that systematically advantages corporations over communities. This competition is a localized form of what geographer David Harvey terms the “spatial fix,” where capital moves to exploit new, more profitable sites (Harvey, 2001). Here in the DMV, Virginia was leading the race, and in response Maryland entered by enacting the Qualified Data Center Program, which grants a 100% sales tax exemption on equipment for up to 20 years — a staggering subsidy (Maryland General Assembly, 2024).

Second comes the revenue illusion and the cost shift. The promise of future property tax revenue is used to justify forgoing sales tax now. Yet even without subsidies, the projected net revenue is a myth because the public costs for new power plants, transmission lines, and water infrastructure required to feed the outsized demands of these gargantuan data centers are socialized across all ratepayers. In Loudoun County, Virginia, the utility has proposed $5-8 billion in new grid investments primarily for data centers, costs passed directly to all Virginians through higher bills (Vogelsong, 2023). This is not general inflation; it’s a regressive wealth transfer, subsidizing a trillion-dollar industry’s infrastructure with residential payments. This skyrocketing demand creates an inescapable public crisis. As scholars Matt Huber and Holly Buck note, this is precisely the kind of challenge that historically gave rise to public utility regulation — a framework designed for long-term planning, socialized investment, and guaranteeing public access over private profit.

Faced with this reality, a common deflection emerges: since grid costs (and thus electricity bills) might rise anyway, shouldn’t we grab the “revenue pie?” This argument ignores the qualitative leap in scale that will be socialized among ratepayers in the specific region the data center is built. Marylanders, including those in Prince George’s County, are already grappling with rising utility bills due to broader inflationary and energy market pressures; this real pain makes the community especially wary of any new costs. In addressing this pain, we must be clear: the exponential demand from data centers does not simply add to this existing trend — it represents a fundamental change in scale and purpose. These facilities are load giants that require utilities to build billions in new, dedicated infrastructure on an emergency timeline (Mattera & Tarczynska, 2022).

Regulatory decisions then allow these massive capital costs — incurred specifically for the highly profitable tech industry — to be socialized across all residential and commercial ratepayers. The majority of the inputs are local and are socialized locally, meaning that if a data center is built in Landover or Upper Marlboro, those costs will be borne by the Pepco ratepayers in Montgomery and Prince George’s counties — both raising residential rates and adding to the list of systemic barriers that prevent other businesses choosing to establish themselves in the county.

This is not merely "rising costs;” it is a regressive wealth transfer, where residents and local businesses are forced to subsidize the private infrastructure of the world’s largest corporations. As Maryland’s own Office of People’s Counsel warned in 2023, this constitutes an “inappropriate subsidization” from everyday bill-payers to tech giants, a dynamic starkly evident in grid planning, where the majority of new regional transmission needs are directly attributable to data center growth (PJM Interconnection, 2023). The question isn’t whether Marylanders pay for grid updates, but whether we will unjustly bear the lion’s share of costs for an industry that can and should pay for itself.

This is not a hypothetical risk but an immediate crisis. In November 2025, the independent watchdog for the PJM grid — the very operator planning these upgrades — filed a federal complaint, labeling PJM’s plan to connect data centers it cannot reliably power a “regulatory grenade.” The complaint warns that this policy, driven by data center demand, directly heightens the risk of blackouts for 65 million customers while funneling windfall profits to grid operators.

In 2024 alone, consumers across seven PJM states paid an additional $4.4 billion in transmission upgrades specifically for data centers (Riccobene, 2025). As with stadiums and big-box retail deals, the promised windfall fails to materialize, leaving budgets in worse shape. Prince George’s County’s own 2025 Task Force Report revealingly contains no substantive net revenue analysis.

Thus, the cycle concludes by deepening the crisis. The resulting fiscal shortfall creates political pressure to approve more data centers on better terms for corporations, locking the community into perpetual extraction. Our socialist desire for well-funded schools and services is weaponized to justify a deal that undermines those very goals.

The only way to avoid this destructive pattern is to reject this false choice: we must demand profitable corporations pay their full freight to fund social programs, not be exempted from them. The path to revenue is through taxing wealth and profit at its source, not through corporate surrender.

The targeting of Prince George’s County for data center development is not an anomaly, but the latest chapter in a long history of environmental racism and systemic disinvestment that has shaped the region. To dismiss the latest push as mere "economic development" ignores this bitter legacy. The county’s status as a politically powerful, majority-Black jurisdiction has, paradoxically, made it a perennial target for developers counting on a "business-friendly" climate when pursuing extractive deals that wealthier, whiter communities would reject.

This pattern was set decades ago. In the mid-20th century, the construction of the Capital Beltway and other major highways physically carved up and displaced Black neighborhoods in Prince George’s, a national story of infrastructure-driven disruption repeated locally. This was compounded by federal redlining policies that systematically denied mortgages and investment to Black residents, stifling generational wealth and designating areas as "less desirable" — except for siting the region’s destructive infrastructure (Rothstein, 2017).

The result was a sustained targeting of the county as a dumping ground. For years, residents have borne a disproportionate burden of the region's unwanted facilities, from landfills and sewage treatment plants to power plants and transmission lines, often with little community benefit. This history is also marked by powerful resistance, most notably when residents successfully organized in the 1990s and early 2000s to defeat a proposed waste incinerator in Largo — a landmark environmental justice victory that protected public health (Hill, 1988).

This enduring struggle reflects a national truth documented by scholar Dr. Robert Bullard in 2000: that race remains the most significant predictor of where toxic burdens are placed. The fight against the incinerator proved community power can win. Today, the push for data centers — with their massive demands on land, water, and energy — is not a break from this past, but a direct continuation of it, demanding the same vigilance and organized power to confront a 21st-century extractive threat.

Data centers are marketed as a “clean” industry, but in reality they function as a classic “locally undesirable land use (LULU),” consuming vast tracts of land and staggering amounts of energy and water while providing few local jobs. The very communities that once mobilized to defeat a toxic incinerator are now told to welcome the power-guzzling infrastructure of Amazon and Google. The threats may be updated — diesel backup generators, the relentless drain on the grid and watershed, the constant hum and industrial glare — but the outcome remains familiar: an erosion of quality of life and a strain on public resources, all without proportional benefit.

The fight emerging in Prince George’s County today is a direct continuation of the peoples’ decades-long struggle for environmental justice and self-determination. It is a fight against becoming a sacrifice zone for the digital age. And it is a fight that can be won, building on the legacy of past resistance. That legacy isn't just historical; it's active. In a recent and significant local victory, community advocates who would have been directly impacted by a proposed data center successfully challenged the county in court. In Bartolomeo vs. PG County (C-16-CV-24-003613, unpub), the Circuit Court ruled that a county bill creating a special zoning exception for a data center on a single parcel constituted unlawful “spot zoning,” blocking the project. This small win proves that organized community power remains the essential tool to defend the county’s future.

A socialist analysis leads to the following platform of opposition and reconstruction. These are immediate, defensive demands — a viable alternative framework within the current capitalist paradigm from which to fight.

What we oppose:

What we fight for:

The urgent fight against extractive data centers requires a bold, socialist alternative: the democratic public ownership of the digital infrastructure defining our century. This model transcends mere regulation, reimagining infrastructure as a democratically controlled public utility rather than a vehicle for shareholder profit. Its logic is grounded in both historical precedent and contemporary necessity, offering a clear path to subordinate technological power to the public good.

The case for this transformation begins with the nature of the technology itself. As Huber and Buck (2025) argue, the massive foundation models powering the AI revolution share the core characteristics — high fixed costs, metered access, and essential public function — of traditional utilities like electricity. Their conclusion, in "Treat AI Like a Public Utility," logically extends to the infrastructure that powers it.

A degrowth perspective that rejects such resource-intensive computing as unnecessary and inherently not part of a democratic socialist future is a valid and compelling alternative not addressed in this article (Schmelzer et al., 2022). But for those who believe this infrastructure could be responsibly harnessed to improve human life, its corporate control is untenable.

The choice is not between corporate efficiency and state bureaucracy; history provides a better model. The early-20th-century "sewer socialists" of Milwaukee demonstrated that municipal ownership of essential systems could be both more efficient and more popular than private alternatives because it was directly accountable to the public. This model finds a modern prototype in Chattanooga, Tennessee’s municipal fiber network, operated by its public power utility, EPB, which prioritizes service and equity over profit. Conversely, the failures of corporate, investor-owned utilities in the energy sector — prioritizing profit over reliability, affordability, and decarbonization — offer a stark warning against repeating this mistake with digital infrastructure (Feldman et al., 2023).

From this analysis, the core principle is democratic accountability. A socialist model roots control in the community through transparent governance and participatory planning. If a community bears the socialized costs of infrastructure — from grid expansion to environmental impact — it must also hold the equity and reap the benefits. A community-owned data center, chartered to prioritize public benefit, would end cycles of corporate welfare. Its operations could be bound to mandates like 100% renewable power and providing low-cost "public shelf space" for community data.

Critically, public ownership provides a structural antidote to the harms of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019). An ethical charter could prohibit leasing capacity for mass surveillance or manipulative data harvesting. By controlling the infrastructure, a community can mandate new paradigms, such as compensating individuals for data use or allocating computational power to public goods like health research, open-source projects, or cultural archiving — rather than optimizing ad-targeting algorithms.

Extending this "digital sewer socialism" to data centers creates a framework for a just transition. As Huber and Buck advocate, it can anchor a public jobs program in maintaining public AI and green infrastructure, offering a democratic stake in the technological future.

The financial architecture for this is achievable, drawing on proven mechanisms. Foundational investment can come from public capital and the guaranteed tenancy of "anchor institutions" like universities and hospitals, a strategy proven by the Evergreen Cooperatives in Cleveland, Ohio. Broader public buy-in can be fostered through community investment bonds, while mission-driven lenders like community development financial institutions (CDFIs) can provide capital, creating a virtuous cycle of reinvestment.

This alternative rejects the false premise that community needs require either corporate catering or regressive taxation. Revenue can be generated by reclaiming wealth from extractors: through land value taxes on speculative gains driven by public investment (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2023), boldly progressive corporate and wealth taxes, and mandates for community benefits agreements and public equity stakes in large developments (Kelly, 2012). These are practical tools to fund public goods without burdening working-class households.

This vision is the logical extension of successful policy and a necessary response to technological change. Just as New York's Build Public Renewables Act empowered its public power authority to build renewable energy (NY State Senate, 2022), we must empower communities to build democratic data infrastructure. The fight, therefore, is to popularize a superior alternative: infrastructure owned by the public, guided by democracy, and dedicated irrevocably to the common good.

The fight over data centers is a microcosm of the larger class struggle. It is a fight over who benefits from technological change, who decides the future of our communities, and who bears the costs. A socialist vision for the future includes public ownership, reclaiming community wealth and building a community reflective of residents’ desired way of life. This vision replaces the hollow choice between corporate plunder and alienated bureaucracy with a system of genuine democratic control and accountability.

By naming the problem as extractive capitalism, articulating a vision of democratic ownership, and pointing to concrete fiscal and development alternatives, socialists can provide a clear political home for the anger and organizing emerging in communities like Prince George's County. The cloud is not above us; it is being built on ground we must fight for.

For additional information on alternative financing structures: Community Solar/Energy Bonds: Cooperative Energy. (n.d.). Our Projects. https://cooperativeenergy.coop/community-solar/(This provides a concrete, local example of community-funded energy infrastructure). CDFIs and Green Lending: The Opportunity Finance Network. (n.d.). Our Work. https://ofn.org/(This is the national network of CDFIs, providing a source for understanding this financing mechanism); Benefit Corporation Structure: B Lab. (n.d.). What is a B Corp?https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/what-are-b-corps/(This explains the legal framework for a mission-driven corporate structure); Bozuwa, J., Mendelevitch, R., & O'Neill, S. (2023). The Public Utility Renaissance: A Framework for Democratic Power. The Climate and Community Project. (This report is the modern socialist playbook for public ownership. It doesn't just argue for public power; it details the "how," including strategies for municipalization, forming new public power districts, and governance models for democratic control. It directly addresses how public ownership is essential for a rapid, just transition to renewables and for ending the utility death spiral caused by corporate investors.)